A Message from the Dean | Reconsidering Our Foundations: A New Beginning

POSTED ON: September 3, 2020

Welcome to the fall semester of 2020! And a special welcome to the Class of 2025; after just one day of classes, they have already made history by being our first group of students to enter the halls of The Cooper Union online. Ironically, they are also the first to be inhabiting our new studio spaces for what I hope will the entire academic year, but removed from the very faculty and catalytic studio culture those spaces elicit. Instead, the Class of 2025 will form a new culture with upper-level students, stemming from the hybrid learning environment set in motion this year.

Some months ago, at the height of the spring semester, the sheer urgency of the pandemic, the novelty of engaging with each other remotely, and our insistence on overcoming isolation was all fresh. It is fair to say now that the new normal—though one that changes seemingly daily—has set in, and it has shown its limits. The coming year will require patience, resilience, and care, along with new ways of learning, teaching, and interacting with each other.

We launched the summer to the news of the murder of George Floyd, and we have ended it with the Kenosha shootings that are a testament to the divisiveness within our country, and the need for discourse and intellectual mediation. We knew we were living through historic times five months ago, but now we are reminded that we must confront this evolving history on a daily basis. I refuse to naturalize the state of affairs as we see them, and I ask you to join me to imagine all the ways in which this moment requires radical reform.

In this spirit, our summer has been purposefully engaging, filled with added work that is important to share. Many students, faculty, and alumni—among others—have contributed to the collaborative work underway. The launch of the School of Architecture’s Anti-racism Task Force has served as a fulcrum fordialogue around a range of issues that have not only been the center point of national cultural conflict this summer, but are also deeply embedded in its ideology. For this reason, probing our own educational model is a critical point of departure for situating ourselves within this important conversation.

The task force led a series of discussions that has resulted in a manifesto and a call to action to build a Cooper Union free of racial and social injustice. My charge to the committee was to reckon with the state of affairs in the world, to position them within our own halls, and to imagine two temporal frames though which we might build change together: first, the urgent, the here and now—this semester, with ample space for experimentation and a tolerance for failure; second, with a longer view in mind, to imagine ways in which our own institution can change its very operations and pedagogies and, in effect, to de-colonize in a fashion that has sustenance. These meetings are not over. They will continue once a month and there will be ample time and space for others to contribute to them.

There are many dimensions to this work, and much of it is pedagogical. We have explored may ways in which history/theory, structures, technology, and professional practice may develop critical ways of working together. More importantly, we have also begun to reassess our relationship to the canons of Western culture, to situate ourselves in a culture of global diversity, to rethink the theoretical lenses through which our work is assessed, and to instigate conversations about power, labor, equity and, of course, the legacy of systemic racism in the United States and how it is embedded within the very foundations of many institutions.

My charge to the faculty has been to revisit the curriculum and, in turn, their respective syllabi, to effectively communicate the relationship between the discipline of architecture and its social engagement. Naturally, in the arena of history and theory, the immediacy of the political implications by which architecture is impacted by policy, practice and shaped by economic forces is palpable. In the studio these connections tend to occur at an arm’s-length, and students have not relented in reminding us of the responsibilities that come with design. Lest we polarize between social engagement on the one hand, and the ‘autonomy’ of form on the other, what I hope will emerge and evolve over the next two semesters are some of the nuances that design entails, at once invested in the discrete technicalities and operations embedded in the generative and representational process, but also how each and every one of them are already deeply political in their composure.

If, at the urbanistic level, questions of zoning and code offer a framework for governing urban form, we have also seen ways in which mapping strategies of redlining and up-zoning have clever, though nefarious, ways of finding loopholes in their techniques to demonstrate the sheer power of formal and spatial operations—in effect giving form to inequities, prejudices, and the kind of disparities from which we suffer today as a society. Certainly not all architectural operations may be as legible as that. Couched in the more abstract syntactic and semantic traditions of architecture there are yet other practices that insinuate culture, orientation, and debate, the political implications of which are often more subtle, co-optable and even malleable. Moreover, these often become visible at a meta-discursive level, and tend to be missed on certain radars. We must ensure that they are not lost in this discussion.

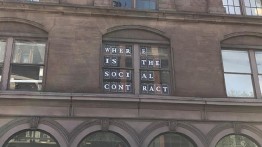

The implications of the matters at hand were embodied in various ways over the summer, and two mythologies persisted. The first revolves around the development of a personal voice, the freedom of individual expression, and effectively the amplification of the myth of the genius. The second deals with the social contract of architecture to speak to the collective, the public, the civic—to be socially engaged and to represent those who may not have a seat at the table. What I hope emerges out of this academic year is an overcoming of this false dichotomy, such that the development of a personal voice may be in service of something larger, and that the prospect of social engagement is advanced precisely through the very representational mediums in which individual architects become experts, be they through form, space, or materiality.

I want to offer a special thanks to Hayley Eber, who led the Anti-racism Task Force, and to all of the members of the group: Sam Anderson, Taesha Aurora, David Bermudez, Ezekiel Binns, Lorena Del Rio, Bunmi Fagbenro, Gabriela Gutiérrez, Jemuel Joseph, Lauren Kogod, Mokena Makeka, Elizabeth O’Donnell, Angelique Pierre, Sarah Saad, and Ife Vanable. To view the results of their work—A Manifesto and Call to Action to Build a Cooper Union Free of Racial and Social Injustice—please click here.

Nader Tehrani, Dean