Emilie Gossiaux, School of Art Senior Blinded in 2010, Wins National Art Award

POSTED ON: August 15, 2013

Emilie Gossiaux, a senior in the School of Art, has won an Award of Excellence from the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C., it was announced this week. In addition to a monetary award, she will be one of only fifteen selected artists whose work will be part of the In/finite Earth exhibition organized by VSA, the Kennedy Center's international organization on arts and disability, opening at the Smithsonian Institution’s S. Dillon Ripley Center in Washington, D.C. in September. While any student recipient of a national art award would be exceptional, for Ms. Gossiaux it can be seen as recognition for perseverance, determination and courage. Ms. Gossiaux's has won the award for "Bird Sitting," a sculpture she created two years after a traumatic street accident during her senior year in 2010 left her completely blind. In spite of this she returns in autumn to complete her degree and graduate with the class of 2014.

Even prior to her accident Ms. Gossiaux, a New Orleans native who turns 24 in August, had to overcome challenges. An untreatable disorder caused her to start losing her hearing at the age of five, a circumstance that pushed her in the direction of visual communication. "I always dreamed of becoming an Artist," she writes, via email. She attended arts high schools and then came to Cooper Union's School of Art in 2007. But in 2010, while bicycling in Brooklyn, a horrific encounter with a tractor-trailer left her at risk for permanent institutionalization. Her remarkable recovery, thanks to the perseverance of loved ones and her own determination, made national news, including coverage by the New York Times and National Public Radio.

Last Spring Ms. Gossiaux returned to The Cooper Union to complete her undergraduate degree, which she will finish at the end of this academic year. She remains completely blind and gets around with a brace on her left leg, though thanks to a cochlear implant, she can hear and speak. She lives in the East Village and walks to class, sometimes without accompaniment. We took the occasion of Ms. Gossiaux's Kennedy Center award to discuss, via email, the award-winning sculpture, how she continues to work as an artist and the "scary" decision to complete her degree.

At what point after the accident did you start making art again? What was the first thing you created?

I began thinking about, and making, art again in 2012, roughly two years after my accident. At the time, I had put myself into a blind rehabilitation-training program called BLIND Inc. in Minneapolis. There I took travel, cooking, Braille, and computer classes. But my favorite class, by far, was Industrial Arts. My instructor was also totally blind and ran his own wood shop in the city. He taught me how to chisel, carve and run different power tools without sight, including a lathe. He also taught me how to use my hands instead of my eyes to get the ideas out of my head.

What forms of expression did your art take before the accident? And after?

I mostly worked in painting and sculpture before the accident, usually with plaster casting or papier-mâché. Now I primarily work with ceramic clay and plaster. Occasionally I do some woodcarving. I also paint with India ink on paper using a device called the BrainPort, which I use as part of a research study. It's basically a pair of glasses with a small camera attached to the bridge. There is a tongue piece the size of a postage stamp that I place on my tongue (the most tactilely sensitive part of the body) that uses electrodes to "draw" the contours of the shapes seen by the camera in real time. It's a process called sensory substitution.

Have your processes changed since the accident?

Usually I would begin by sketching my ideas for sculptures or paintings with pen on paper. I've come up with new ways of doing the same thing. Now, I take a flat slab of soft clay and draw into the surface by hand or with the wooden end of a paintbrush. This way I'm able to feel the drawing tactilely. The BrainPort also helps me get my ideas out on paper, even if in very simple line drawings.

Are your motivations for making art the same as always?

My motivations are still the same: to make beautiful things for people to experience.

What sort of aesthetic choices do you find yourself making now that you didn't before, if any?

Unless I am creating a representational object, I don't think about color much anymore. I stick to using white or black. I mostly focus on the different kinds of textures and surfaces I can create. Even before my accident both my paintings and sculptures were heavily focused on texture and touch. I believe that whatever it feels like, it looks like too. If it feels good then it looks good.

As an artist I imagine you were long used to being influenced and energized by other artist's creative works. How have you adapted this need now that all purely visual artworks would seem to be unavailable to you?

I still enjoy reading about other artist's conceptual works and ideas, and listening to the audio descriptions of other artist's works. I also attended a ceramics show with Betsy Alwin, one of my instructors from Cooper. She was a friend with some of the artists in the show and they allowed me to touch and feel their sculptures. I was very inspired by feeling the textures and forms of the pieces in that show. Another artist who really motivates and inspires me is my friend/mentor Daniel Arsham (A'03). Over the Summer I have been working in his studio, where he is sharing his space so I can work on my own ideas for sculptures. Sometimes he takes me to galleries and he'll walk around with me and describe the paintings or sculptures in the show.

Can you please take me through the decision-making process to return to school and finish your art degree?

At first it seemed impossible and scary. I really didn't want to go back to school. I doubted whether I could do it at all. It only became possible after I went to BLIND Inc. and met other ambitious blind people. I met two other blind artists who worked with me and taught me how to work with my hands again. My instructors there pushed me to try new things and to think about art differently. I really owe it to everyone there for helping me.

How did they push you to think about art differently?

When I started attending Blind Inc. in 2012, I was still really unsure and unconfident of whether or not I wanted to continue my career as an artist. But all of my instructors at the center believed in me, and it was really helpful to have everyone pushing and nudging me forward to regain my confidence as an artist. My braille instructor, Emily Wharton printed out some Critical Art Theory textbooks for me in braille and had me write my own essays about them. My industrial arts instructor, George Wurtzel took me to his friends' studios and introduced me to other artists in the city. He was also the one who taught me how to make sculptures by carving wood. I never considered creating art with wood as a material, but I really found myself loving it. And finally, my careers instructor, Dick Davis pushed me to sign up for night classes at a Ceramics Studio in Minneapolis. At first, I was really nervous about taking the class, because it was the first time where everyone else in the class was sighted, so I felt a little uncomfortable. But I was able to work and learn just as fast as everyone else in the class and became really good friends with my Ceramic teacher, Glynnis Lessing. The class only lasted 6 weeks, but I ended up signing up for the class again for another 6 weeks.

You've already started by taking some classes at the School of Art last year. How did it go?

I love Cooper Union and have always loved Cooper Union. There is no other school better suited for me. It works well because of it's size—small—and the community of students all know each other intimately. All the professors and staff and students have been extremely helpful and understanding of my needs, capabilities and limitations. Many of the staff and professors have given me extra time to work with them one-on-one. Shout out to Betsy Alwin, Gwen Hyman, Lisa Lawley, Zach Poff, and Sara Jane Stoner—all exceptionally wonderful and extraordinary instructors. I really love working with all of them.

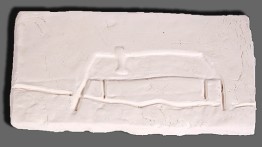

Tell me about the artwork you submitted to the Kennedy Center

The idea came from one of the first drawings I did with the BrainPort. It started as a drawing of two hands folding into each other, sitting on the seat of a chair. I looked at the drawing a little bit closer and the fingers appeared as bird wings, and the thumb appeared as a head. So I quickly drew a beak and it became a fat looking bird sitting on of a chair. I liked the looseness quality of the drawing and how one image could easily become two. I was interested in that quality of illusion. Anyway, when I went back to Cooper, I decided I would make a sculpture out of it. It was nice because it came about in the same way I always thought of ideas for sculptures. I would sketch them out, and use the drawing as inspiration for the three dimensional object.

What was your reaction upon learning of the award from the Kennedy Center?

I've never really won an award for my work before, so I was really excited and surprised. I found out when I was visiting my family in New Orleans. I immediately text messaged Betsy Alwin, who helped me submit my work to the contest.

What are your long-term goals?

Stay in the city, rent a studio, and keep finding new ways of making art!