Anthony Vidler: Origins of Study

Sat, Jan 27, 2024 6:30pm - Wed, Feb 14, 2024 7pm

On view in the Third Floor Hallway Gallery, this exhibition presents, for the first time, formative studies, drawings, and photographs by former dean and professor Anthony Vidler (1941 – 2023). Early in his deanship of the School of Architecture, Vidler gave the lecture A Short Life in Architecture to Cooper students and faculty. The talk summarized his trajectory within the discipline of architecture, including his nascent study of the field:

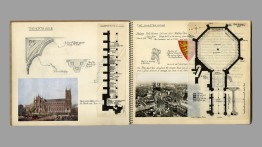

I first decided to “be an architect” at the age of 14. Inspired by one of those early-teen books in a series called, I remember “Let’s Go Look at Buildings,” I mounted my bicycle and pedaled all over the county of Essex sketching Anglo-Saxon, medieval, and neoclassical churches, rubbing impressions of brass effigies of knights in armor, recording inscriptions, and, believe it or not, even at that tender age, composing a “handbook” to the architecture of the region, illustrated and penned by hand. Kids were really weird back then.

But one thing led to another, and I was soon hot on the trail of earlier and more exotic histories, and the public library lending service provided folio volumes—the multi-volume publication of Flinders Petrie on the excavation of the pyramids; the full-size reproduction of Villard de Honnecourt’s journal of medieval masonry (both traced in full as a way of having them to keep so to speak) and most important of all, the folio publication by the late 19th century engineer Auguste Choisy of Hagia Sophia, the axonometrics in which, again carefully traced, formed the center of a short prize essay on the origins of the Byzantine “squinch arch”—that little quoin at the corner of square walled enclosures that joins them to the circular domes above.

It should probably be mentioned that if I had known of the life of Marcel Proust, my own intensely nerdish and asthmatic childhood, often confined to bed for weeks at a time, would have looked remarkably like his.

But perhaps the most formative experience of all was a school trip to Europe—a very rare thing at the time, so soon after the close of hostilities in World War II—when we took the train to Venice, Florence, and Rome (three days in each place) and I carried with me a little bellows camera (2 ¼ x 2 ¼, black and white) with a Zeiss lens that I had won from Kellogg’s cornflakes box tops, and a book recommended by my indefatigable public librarian to prepare me for Venice—the three volumes of Ruskin’s "The Stones of Venice." Venice was thence to remain, as it does today, a fulcrum of my passion for architecture. I returned for six months in the interval between high school and college carefully eking out a little money earned by clearing stones of Ticino fields, living in a little room behind the clock that overlooks the Piazetta, and diligently documenting every Gothic palace façade in sketch and photograph, unwittingly preparing myself for my encounter with Colin Rowe and his fascination with facades.

Shortly before his death, Tony proposed a hallway gallery exhibit derived from his personal archive, specifically his early travel photos from his trips to Venice in 1956 and 1960, when he was just a teenager training himself to document and study works of architecture through photography and drawing. Found within Tony’s loosely sorted collection of photos was a business envelope filled with 2 ¼ black and white negatives annotated: To Venice 1960 | Venice Etc. 1960. Once digitized, the images revealed that Tony had not just surveyed Venice but had also traveled to other parts of Italy from his temporary Venetian home base in the six months before he entered Cambridge University.

Tony’s papers also included studies from the years leading up to his second trip to Venice: surveys of parish churches in the English countryside that he referred to in his lecture, as well as studies of Westminster Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral, undertaken between 1956 and 1959. What is incredible about these materials—a combination of descriptions, drawings, and photographs—is that they were made when Tony was just 15 to 18 years old, before any formal training in architecture. They demonstrate his self-motivated, self-directed determination to learn early on how to read works of architecture by studying their history, representing them through plans and sketches, and analyzing their structure. The surveys are accompanied by drawings Tony made of structures and landscapes he encountered as he traveled from church to church. Along with his travel photos and their associated drawing studies, they are, collectively, an incredible testament to Tony’s burgeoning passion for the discipline of architecture and his thirst for the study of architectural works.

As we celebrate Anthony Vidler for his generational impact on the history, theory, and pedagogy of architecture, we look back to contemplate the origins of his journey into a transcendent life in architecture.

----

The exhibition opened in conjunction with Anthony Vidler—A Celebration, held on January 27. On view in the Foundation Building's Third Floor Hallway Gallery. Open to Cooper Union students, faculty, and staff.

Located at 7 East 7th Street, between Third and Fourth Avenues