Senior Snapshots 2015: The School of Art

POSTED ON: May 19, 2015

For the second in our 2015 series of "Senior Snapshots" focusing on each of the three schools at The Cooper Union [see parts one and three] we visit with a few of the graduating seniors from The School of Art. Stephen Gurtowski, Elzie Williams, Maria Rodriguez-Jimenez and Omari Douglin talk about how they got here, what they focused on in their senior presentations, and where they are headed next.

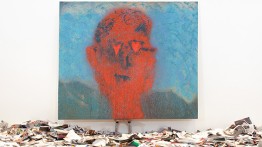

It was only natural that Stephen Gurtowski (left) and Elzie Williams (below right) would collaborate on their senior presentation. After all, they have produced a collaborative exhibition every year since they met as freshmen. It doesn't matter that their practices use different mediums and address different concerns. Somehow the works complement each other. By all accounts their culminating effort, "Everything Must Go," was their greatest success.

It was only natural that Stephen Gurtowski (left) and Elzie Williams (below right) would collaborate on their senior presentation. After all, they have produced a collaborative exhibition every year since they met as freshmen. It doesn't matter that their practices use different mediums and address different concerns. Somehow the works complement each other. By all accounts their culminating effort, "Everything Must Go," was their greatest success.

"I am definitely a painter," Stephen says. "I believe in a certain kind of truth that can only be expressed through painting. That's the part of the art world that I engage with most. My paintings come from my personal experiences and relationships and are often autobiographical but speak outward to more general subjects."

"I make collages," Elzie says. "Ever since high school I knew I wanted to make things with my hands with paper or collage materials. My pieces explore the dialogue between color and race relations."

Both Stephen, who grew up on Long Island's North Shore, and Elzie, who grew up in Baltimore, have followed artistic paths that started early. "My elementary school art teacher thought I had a knack for it," Stephen says. He took after-school art courses and eventually wound up in the high school Outreach Program run by the School of Art. Elzie likewise got early encouragement and eventually attended the Baltimore School for the Arts, where The Cooper Union was well known.

"Everything Must Go," their senior presentation, brought their practices together in an environment they designed for maximum audience engagement. They covered the entire floor with thousands of magazines, a by-product of Elzie's work. "I look for pages where the front and back of a page correspond. The front contains an image of a person and the back is a solid color." Once he amasses enough matching dual-sided clippings, Elzie then tapes them to each other as one sheet and presses the sheet between two pieces of Plexiglas. These sheets stick out perpendicularly from the walls of the gallery, exposing both sides.

"Everything Must Go," their senior presentation, brought their practices together in an environment they designed for maximum audience engagement. They covered the entire floor with thousands of magazines, a by-product of Elzie's work. "I look for pages where the front and back of a page correspond. The front contains an image of a person and the back is a solid color." Once he amasses enough matching dual-sided clippings, Elzie then tapes them to each other as one sheet and presses the sheet between two pieces of Plexiglas. These sheets stick out perpendicularly from the walls of the gallery, exposing both sides.

Amidst the sea of magazines Stephen's paintings were hung, leaned on a stool, or in one case, strapped to a pole. One light-hearted work entitled "Water Skier" evoked a self-portrait, but with hearts for eyes. "As part of the process, I put paint into spray bottles, like Clorox bottles, and sprayed it on the surface. The action reminded me of the qualities of water. Ultimately, though, it's about love."

Visitors kicked the loose pages like leaves. Some lay down and made angels like children in the snow. "We just wanted to have fun with the space for our last show," Elzie says. "Cooper provides a rare opportunity to have complete creative control over how your show looks."

After graduating Stephen will start an MFA program at New York University. Elzie will stay in the city, working and building his portfolio. They plan on continuing their collaborative exhibitions into the future. "Our work isn't related in any physical way. But it always seems to work better when shown together. It resonates with new meanings," Stephen says. Elzie concurs. "We are always working towards another show. We are always going to be in communication with one another.”

Maria Rodriguez-Jimenez grew up in Cuba until she was 12. Her grandfather, who arrived during the Mariel boatlift, sponsored her father and his family to move to the U.S. First she lived in New Orleans but then moved to Miami. Growing up, her older sister liked drawing, but Maria did not take an interest in it. After high school Maria went to a community college to study biology. Two years passed and then…

Maria Rodriguez-Jimenez grew up in Cuba until she was 12. Her grandfather, who arrived during the Mariel boatlift, sponsored her father and his family to move to the U.S. First she lived in New Orleans but then moved to Miami. Growing up, her older sister liked drawing, but Maria did not take an interest in it. After high school Maria went to a community college to study biology. Two years passed and then…

"Biology just wasn't for me," Maria says. She had been taking art classes and discovered a talent she hadn't explored much before. "I went to a portfolio review. I didn't know anything about Cooper. My friends told me, 'Oh nobody gets into that school. They are super-competitive.' I decided I might as well show my portfolio. I showed it to Scott Nobles. He's a print-maker and teacher here. He said I should apply." And so she came to the School of Art, where her life and art took another turn.

"When I first came here, my work was very figurative and realistic," Maria says. "Now they are almost completely abstract except for some some representational elements. I use silkscreens to ground the abstraction so it is not just minimalist. I am no longer so interested in telling a story. I am trying to express a feeling. I am not interested in being direct because then I might as well just write and post that somewhere."

As a recipient of a Benjamin Menschel Fellowship that funds projects proposed by upperclassmen, Maria got the chance to return to Cuba last summer. She partnered with Pedro Galindo-Landeira, a third-year student at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the time and a fellow Cuban native, to explore life around the U.S. / Cuban land border at Guantanamo. They spent a month videotaping what they found.

"It's very strange," Maria says. "There's a lot of surveillance. I've always been interested in the uses of surveillance in video. But when we came back we wanted to make a project that wasn't so directly about Cuba. So we made this fence on the seventh floor because we felt the fence that consumes Cuba relates to what's happening at Cooper, in political terms. We blockaded the whole floor for two hours. You had to take the elevator to get from one part of the floor to the other."

That fence then got integrated into Maria's senior presentation in a subtle way. The untitled show included large paintings scaled to Maria's own height. Three of them used the fence poles as stretchers, slightly warping the canvas. "The poles reinforced the presence of the frame and thus the object within the painting surface," Maria says. The front contained fields of white, black and raw canvas with silkscreen elements, part of an ongoing investigation of the color black. "Black is the only color that allows me to understand abstraction in reference to my identity as an immigrant and my identity as a painter in the history of painting."

After graduating Maria will be traveling to Marfa, Texas for thee weeks as part of a program called Marfa Summer School in which six students from Cooper will join students from the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. Marfa was made famous by the artist Donald Judd (1928 - 1994), who realized large scale works in a series of buildings in a vast desert landscape. Students will study in both classroom settings as well as in the field making work to be presented in a exhibition at the program’s conclusion. After that she plans on looking for a job and finding a studio to continue her artwork. Eventually she may apply to graduate school.

"I've changed a lot," Maria says, reflecting on her time at The Cooper Union. "Definitely my discovery of art history and contemporary art influenced my paintings a lot. I was very artistically naïve when I got here. But also the experience of being in the studio with everybody else was key. I thought it would be a competitive environment, but it is more a community of students and faculty. I think a lot of people have said that and it is very true. The fact that it is a community is very helpful because people give you honest critiques here. They don't try to bring you down to make themselves feel better. Which is the best thing because you learn a lot.”

While The Cooper Union is well known for being very challenging to get into, Omari Douglin has done it twice. Born and raised in Brooklyn, he began showing artistic promise in middle school and later went to New York City's Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. After that he passed the hurdle of acceptance to The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. But a year later he decided the School of Art's pedagogy better matched his evolving interests. And so, as per the requirements of each school at The Cooper Union, he applied again and was accepted, starting over as a freshman.

While The Cooper Union is well known for being very challenging to get into, Omari Douglin has done it twice. Born and raised in Brooklyn, he began showing artistic promise in middle school and later went to New York City's Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. After that he passed the hurdle of acceptance to The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. But a year later he decided the School of Art's pedagogy better matched his evolving interests. And so, as per the requirements of each school at The Cooper Union, he applied again and was accepted, starting over as a freshman.

"In the beginning I was more of a minimalist," Omari says. "My sensibility was all about functionality and things being clear and straightforward. That informed my interest in architecture. Then as I learned about art history, and wanting to further that history, I tried to synthesize that history into figuring out what was important to me. I went from being a minimalist painter to being a more representational painter."

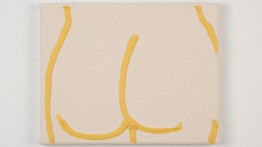

Omari found his source of personal expression through the subjects most grounded in the tradition of painting: the figure, landscape and still life. His senior presentation, "xoxo," mounted in the 41 Cooper Gallery, shared the space with the work of fellow senior Isabel Legate. Her sculptures took up the floor and his paintings took the wall. One group of canvases, all measuring 8x10 inches, are referred to by the artist as "the butt paintings," or more precisely, "super-simple line drawings of the female form." Each is made up of only a few lines created out of an extremely thick and unusual artistic material.

"It's caulking," Omari says, "the stuff you use for sealing cracks and gaps. I was using it as a substitute for oil paint because I like its sculptural quality. It looks like sculpture and painting at the same time. Also I have to use a caulk gun to get it out so it is pretty challenging to control the line work. But I like that challenge."

The group of larger canvases combines figures, elements of the landscape and objects formed out of oil paint, oil sticks, spray paint and caulking on a white ground. In "The Creeper," a black figure wearing Nikes seems to be creeping around a cave with a yellow glow that shines through the negative space of his body. It's a fantasy space that could only exist in a painting. "I've been working a lot with the figure and the landscape, trying to bring a freshness to those classic painting tropes," Omari says.

Besides practicing his art, Omari has been working at the studio of the artist James English Leary for the last year, where he will continue after graduating. Omari has also spent four years as a student instructor with the Saturday Program, one of the School of Art's two high school outreach efforts. "That's been really great too, just gaining that experience having to be in a classroom with younger artists and being an influence on them, teaching them things," he says.

How does he look back on his time here? "When I came into the art school I had the freedom to work by myself and do what I wanted to do and explore my own ideas. I feel like I learned a lot. I am definitely a better artist. I know a lot more. I am more aware. I have sharpened my skill set. It feels good to be graduating, to be at a place where I feel confident in my work and continuing my practice.”