Meet the Deans: Mike Essl

POSTED ON: August 11, 2016

Mike Essl. August, 2016. Photo by Leo Sorel/The Cooper Union

In some ways it makes perfect sense that Mike Essl, associate professor, has become the acting dean of the School of Art, and in other ways it seems wildly unlikely. He is one of those alumni who found that the meaning of The Cooper Union informed his entire life, and he wears his passion for the place (literally) on his chest. But he has also been one the most vocal critics of its administration and filed a lawsuit, along with others, against the board's decision to reduce every admitted student's full-tuition scholarship by half. We sat down with him for a chat about how he got where he is and what he would like to do while he helms the ship.

Mike Essl, 42, grew up in Willow Grove, north of Philadelphia, except for a three-year stint in Houston, Texas from second to fifth grade. Professionally, he is a graphic designer who is best known for his web design, a practice he started while still a student. Even before graduating from the School of Art in 1996 he was hired as art director for the launch of duracell.com. Afterward he co-founded The Chopping Block design firm but continued to teach until a fall-out with the shop and a growing sense of discontent with the commercial work he was doing pushed him to "double-down" on teaching. Now he heads the graphic design program at the School of Art. He lives in Crown Heights, Brooklyn with his wife, Mia Eaton, a project resource manager, and his four-year-old son, Mars.

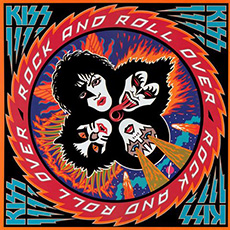

How did you become interested in graphic design? I had this one moment I always remember. I was working in a comic book store and I got interested in this Kiss comic because my boss at the time said, "Check this out. When they printed this, Kiss put their blood in the red ink." I remember thinking, "That's really weird." I went to my dad's collection of LPs to see if he had any albums and he had this one Kiss record, "Rock 'n Roll Over." The cover is by Michael Doret [A'67]. It was like an explosion. I thought, "I want to do this. If you can make money doing this, I want to do whatever this is." So I took the record to my school library and asked, "What is this?" and they only had one book, Milton Glaser: Graphic Design by Milton Glaser [A'51]. So all these Cooper connections started to happen before I even knew it.

I had this one moment I always remember. I was working in a comic book store and I got interested in this Kiss comic because my boss at the time said, "Check this out. When they printed this, Kiss put their blood in the red ink." I remember thinking, "That's really weird." I went to my dad's collection of LPs to see if he had any albums and he had this one Kiss record, "Rock 'n Roll Over." The cover is by Michael Doret [A'67]. It was like an explosion. I thought, "I want to do this. If you can make money doing this, I want to do whatever this is." So I took the record to my school library and asked, "What is this?" and they only had one book, Milton Glaser: Graphic Design by Milton Glaser [A'51]. So all these Cooper connections started to happen before I even knew it.

How did you end up at Cooper?

I had this arch nemesis in high school. It wasn't like he was confrontational. He was just kind of snotty. I told him I was applying to RISD and SVA and he said, "What about Cooper Union?" And I said, "What's Cooper Union?" And he said, "Well, you'll never get in." There was a portfolio day in downtown Philadelphia. The guy who looked at my portfolio was Norman Sanders. It was an ordinary high school portfolio with still-lives, tempera paintings and portraits like everybody has, and he flips through it really fast and says, "Got anything else?" So I showed him all this design work that I didn't think was what they wanted to see. And he got really interested and asked, "You did this?" And I said, "Yes, I learned Pagemaker on my own and did my own paste up." He asks how I learned to do paste up and I say, "I have this book that taught me." And he says, "Oh, I wrote that book." He became my offset lithography teacher at Cooper. The illustrator of that book was also at Cooper and became my typography teacher. So there is this weird Cooper thread in all my early design experiences. It's like destiny or something. Anyway I got into Cooper and my rival did not.

What was your practice at the time you graduated?

While I was a junior there was an ad posted in the lab and all it said was, "Do you know Photoshop and HTML?" I knew Photoshop well but I had no idea what HTML was. I went to the interview and I lied, "Yeah, I know HTML." I left that interview with the job in hand, went home with a book on HTML, went back in and coded HTML. It wasn't that big of a deal. That job went well and my client formed an agency on the basis of it and I got hired to art direct the Duracell batteries website while still a senior. I had a team of five designers and programmers. It was a crazy time. So that was my practice. I was the web guy.

What came next?

I got lucky because duracell.com had a web game, that some people say was the first. It got a lot of press. And often the angle was, "Punk kid in college designs Fortune 500 website." I started working at Cooper's Design Center when I graduated. But the web work just kept coming so I had to leave after six months. I started my own firm because the money was just too good.

So how did you end up teaching here?

My practice did well. My firm, called The Chopping Block, went from two people to 15 people. It was good. But I just didn't care. I'm not motivated by money, I guess. I wish I knew that then, but now I understand it better. Getting into Cooper… the idea that you could look around and think, "That person goes for free and that person goes for free," was an ideal that changed me. We worked for a lot of entertainment companies -- we designed all the websites for Miramax films -- fun, great stuff, but nothing for the public good. I was teaching adjunct all over the place, including here. I realized that helping students was much more rewarding than client work. So I started picking up more classes. Then I had a falling out with my partners and they canned me, which is a whole other story, but I doubled down on teaching and applied here for a full-time job.

You took a sabbatical while the lawsuit was ongoing. What did you do?

You took a sabbatical while the lawsuit was ongoing. What did you do?

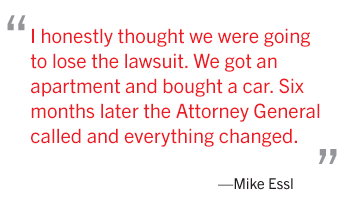

I worked at Mule Design in San Francisco and taught at the California College of Arts. Mule is known for designing large websites for the public good. My two projects out there were to design and project manage a website redesign for the San Francisco Opera. It was a nine-month job. And I also designed a website for the National Audubon Society’s Climate Report about how climate change affects the ranges of North American birds. I went out to San Francisco because I was unable to find a firm in New York that had a similar mission. I knew if I went to Mule the work would be rewarding in the same way that teaching at The Cooper Union is rewarding. I honestly thought we were going to lose the lawsuit. We got an apartment and bought a car. Six months later the Attorney General called and everything changed.

As one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, how do you feel about the progress post-settlement?

I think the morale at The Cooper Union, post-settlement, is much better. It feels like a happier place to work. And I think Bill Mea has a lot to do with that. I think the board doesn’t know what they want to do. I think they are waiting for a new president to tell them what to do. I have a problem with the way the board is handling things. They seem to be going very fast in the presidential search and very slow in the Free Education Committee. But the thing I think is going really well is the increased transparency. Having elected faculty representatives at all the board meetings and a representative in the presidential search will help build community and trust, which we are desperate for.

So how did you end up becoming dean?

I volunteered. The faculty votes on an acting dean. They officially nominated me and voted for me unanimously.

Why did you volunteer?

It seems like a funny time to be at Cooper Union. A time with a lot of change. And since I instigated some of that change I felt like I should step up. Sort of like, "You made a mess now clean it up" [laughs]. I love the place. If a job needs to get done I am happy to do it.

What are your plans as dean?

The thing I think is exciting is that the dean has the potential to help heal the art alumni and bring them back in. I can talk to them about what it would take to get them to come back or donate or help. I don't think there has been a push like that from the dean's office before. I think I am uniquely positioned to do that outreach. I've talked to development and said, "Give me a list of disgruntled people. I'll call every one of them." If I'm back in, they have no reason not to be. At least that's the argument I would make. People ask me every day, should I give to Cooper Union? I used to say, "Wait." Now I say, "Yes."

Anything else you would like to tackle?

We spend a lot of time in admissions with questions about diversity. I have rarely had those conversations happen when we hire professors. I want to talk to people about how we can do better there. Graphic design, for example, is very white. It's unbelievably white. As dean I would like to help make a change there.

Does your new role as dean affect your role as a faculty representative to the board of trustees?

Because I am still technically a faculty member the board has said that legally I can stay as the elected observer for the School of Art. How long that will last is an open question. Because I am the elected observer to the presidential search committee, I think it will last at least as long as the search. I am grateful they let me stay because continuity there is important. But after that I think the art school should elect somebody else, even though my term is another year.

What's the process and timeline for finding a new dean?

Somebody on the faculty will be tasked with heading the search, or two people will be co-chairs of the search. Then they do a national search in conjunction with HR. It will be similar to the last search that hired Saskia Bos. We identify candidates. We invite them in and conduct interviews. That's all at the faculty level. Then we send our recommendations to the president. Part of the timeline has to do with when we get a new president. My understanding is that you often leave deanships unfilled until there is a president in place. So my guess is I will be here for a year, maybe two.

Will you be throwing your hat into that ring?

Definitely not. I am going to teach a class while I am dean. That's what I am here to do. Ideally when the deanship is over I roll back into the faculty and go back to making books and weird websites and teaching students. This question about diversity in graphic design, really the only answer is to teach people to be designers. That's my job: to make more designers. Also I think I'm a great dean for right now. I don't think I'm a 10-year dean.

The school recently announced the hiring of three new full-time faculty members after hiring only one in the previous 11 years. What went into the selection process?

The new faculty hires were an opportunity to consider how we can shape the future of the school. Of the seven tenured faculty, I was the youngest, with most of the others a full generation older than me. So eventually there is going to be a changing of the guard. As a result we cast a really wide net. What's amazing about the three artists we hired is that all three of them could teach across disciplines, which really fits with the generalist model we have at the School of Art, where there are no majors. They are in the art world in a way that none of us are. They are practicing artists who are also committed to teaching. That's rare.

So now that you are dean, how does it feel?

It's intimidating. I'm a little nervous. Mostly because I know graphic design really well but not the art world at large. I'm more excited than scared. It feels like I could make a lot of positive change, but we have to keep our eye on what it means to go back to free and what it means to spend money. Juggling that seems daunting, but there is opportunity there too.